An Intro to Device Authentication and Fingerprinting

In my discussion on zero-trust networks , I mentioned there were three different mechanisms to calculate trust in a network: user trust, application trust, and device trust. Trusting users is a fairly straightforward process; looking at what credentials are being used and a variety of other user statistics at the time of login. Trusting applications tends to lean more towards creating certifiable code, and reproducible builds that are matches on different machines. However, in a large-scale network (VT’s eduroam, for example), identifying and authenticating a particular device can be a little more difficult, especially in an environment where endpoints are not static and users change devices.

When authenticating a user, a service may request a variety of information from that user, such as username/password or certificate. Using a smartcard is a form of user authentication that provides PIN protected certificates to a service. To authenticate a device, however, we want to avoid user input. Think of a smart device that just needs to stay connected to a network, and whose network traffic needs to be authenticated often. Having a user approve that device’s traffic is costly and rather inefficient. Instead, we want hardware or software that is inherent to the device that can be utilized by the device without the need for user input like a PIN or password.

The current standard for device authentication and certificate management is called a trusted platform module, or TPM. Originally proposed by the Trusted Computing Group (TCG), it was adopted as ISO/IEC 11889-1 in 2009, with revisions being published every few years. A TPM is usually a piece of hardware that is integrated into a device that stores private keys and performs encryptions and hashing. The host system is then able to access this hardware through its API. The TPM can be its own standalone chip (discrete), or be integrated with other functions in hardware (integrated). The TCG specifications for TPM 2.0 describe the use of firmware and software TPM’s, but these are somewhat less secure as they are more vulnerable to attacks.

TPM 2.0 made many improvements over the older TPM 1.2. The main vulnerability that was mended in the revision was the use of algorithm agility. Rather than relying only on SHA-1 (which is no longer secure) or on any single algorithm, TCG made TPM 2.0 algorithm agnostic, so that any TPM manufacturer could implement any algorithm to meet specifications. This allows a single piece of hardware to still remain secure even if one of the algorithms becomes vulnerable, granted the systems using the TPM switch to a different scheme.

Many applications use TPM’s for encryption, namely Microsoft’s BitLocker. BitLocker uses keys generated in the TPM to encrypt an entire hard disk. Without the TPM, the OS would refuse to boot, making the system inaccessible without the keys stored in the TPM. Web browsers would even use TPM’s as a source of random number generation and key storage.

The keys generated and stored in a TPM can be used for authentication as well. In the same way a server presents a client a public key to prove its identity, TPMs can present their public key to applications and servers as a way to prove the identity of the device that the TPM is in. This is a reliable form of authentication as it is infeasible to remove a TPM from a mobile device and add it to another device. This physical security brings a significant amount of trust into a connection. A service can maintain a list of trusted devices and their public keys, and perform a handshake with potential devices to determine that the keys are valid. In combination with forms of user authentication, a service can reasonably determine if the connection is allowed or not.

TPMs do not fix devices that do not already have that hardware installed, however. In the case of older mobile devices and laptops, a security configuration described above would cause these devices to be left out, and unable to access the resources behind the authentication. Instead of integrated hardware, older devices could rely on removable keys, such as a Yubikey.

A Yubikey is a brand of hardware authentication device, but is a universal two-factor (U2F) token. To validate a device, a user would plug the U2F token in, and the client-side software would forward the necessary data from the token to the server. While this type of authentication adds another layer of security on top of just standard user credentials, its mobility makes it a little less trustworthy than a TPM. This is because an attacker that has access to a victim’s U2F token could try to authenticate a malicious device, which would be nearly impossible to do with an integrated TPM.

Device authentication is a rather binary process; the device is either authenticated or it isn’t, the certificate is valid or it isn’t. The methods described above depend on unique pieces of hardware to prove an identity. Are there ways to determine an identity of a particular device without such hardware? It turns out that fingerprinting can be used to create a reasonable sketch of a user or device.

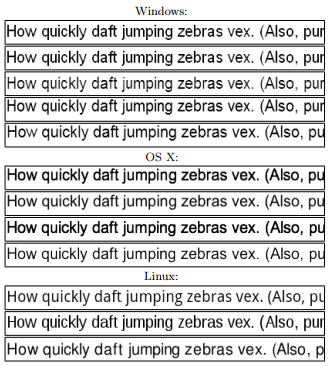

One of the most common forms of fingerprinting is for a browser. Websites collect data from your browser that paints a fairly unique picture that can be used to recognize you for later visits. This process became very common after a paper was published that described using the <canvas> element in HTML5 to identify the configuration of a particular browser. In the study, researchers rendered text on different computers and browsers, and found many differences between the renderings, as shown below in the rendering of Arial 18pt. The use of canvas fingerprinting evolved from text-based to more complex images, where there is more room for bit comparisons, giving more room for uniqueness.

The issue with browser fingerprinting is simple: websites are able to uniquely identify a user without their permission, even after they delete cookies. This makes it rather difficult to remain anonymous on the web. There ways to mitigate this extraction, however, such as plug-ins like Privacy Badger can be used to block the content being presented by such trackers. More generally, you can make your browser more difficult to fingerprint by making your browser less unique. By making your browser one like the rest of the crowd (having the same plug-ins and configurations), you make it more difficult to label your browser as “yours” and not someone else’s. Using a Tor browser also improves your anonymity, although this can cause a whole other slew of issues for a user.

The same technique of collecting information from a browser that is readily available and accessible can be applied to wireless devices as well. Rather than using the user profile to display relevant ads on another website, fingerprinting in a wireless environment can be used to identify a particular device that may not have authorization to connect to the network. Fingerprinting in this case can be done at each layer of the network stack.

At the physical layer, receivers can collect signal strength information during the connection. Other factors like channel width can vary between devices, which can be used to distinguish between devices. However, the physical layer alone is not reliable enough to fingerprint by itself.

In the data-link (MAC) layer, gives way to vendor specific implementations of different standards that allow for some identification. One could even use the MAC address (hardware address) to identify a device, but this is easily spoofed, so should not be used on its own.

In upper layers, we could begin to look at the intervals that packets are sent to distinguish between two devices. Services could also lean on browser fingerprinting to add to the calculations of trust. What is important to note about these methods of device fingerprinting is the need for multiple avenues of identification, rather than depending solely on a single feature. The use of multiple features is key to distinguishing between multiple devices, especially on a wide-area network such as the VT wireless network.

More information about device fingerprinting can be found in this paper by Professor Saad from VT (and others) called Device Fingerprinting in Wireless Networks: Challenges and Opportunities .